In July [20th] 1916 during the Battle of the Somme, poet Robert Graves was struck by a shell and was so badly wounded that the next day he was reported to have died.

He did in fact survive and went on to write about the traumatic experience of war in his autobiography Goodbye to All That.

While his physical injuries healed, the psychological impact lingered. He recounted returning to England and trembling at strong smells, akin to gas, and loud noises.

During a bloody five-day battle, nearly 4,000 Welsh soldiers were killed, missing or injured, putting their division out of action for almost a year.

And the overall five-month campaign in northern France has come to stand for the horror and futility of the First World War.

Shellshock

It is also known for its ‘epidemic of shellshock’, which at the time was generally not recognised as individual psychological trauma, but as a threat to the army as a whole.

But the first steps were taken to look at the effects of what is now known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and develop a more sympathetic approach to treatment.

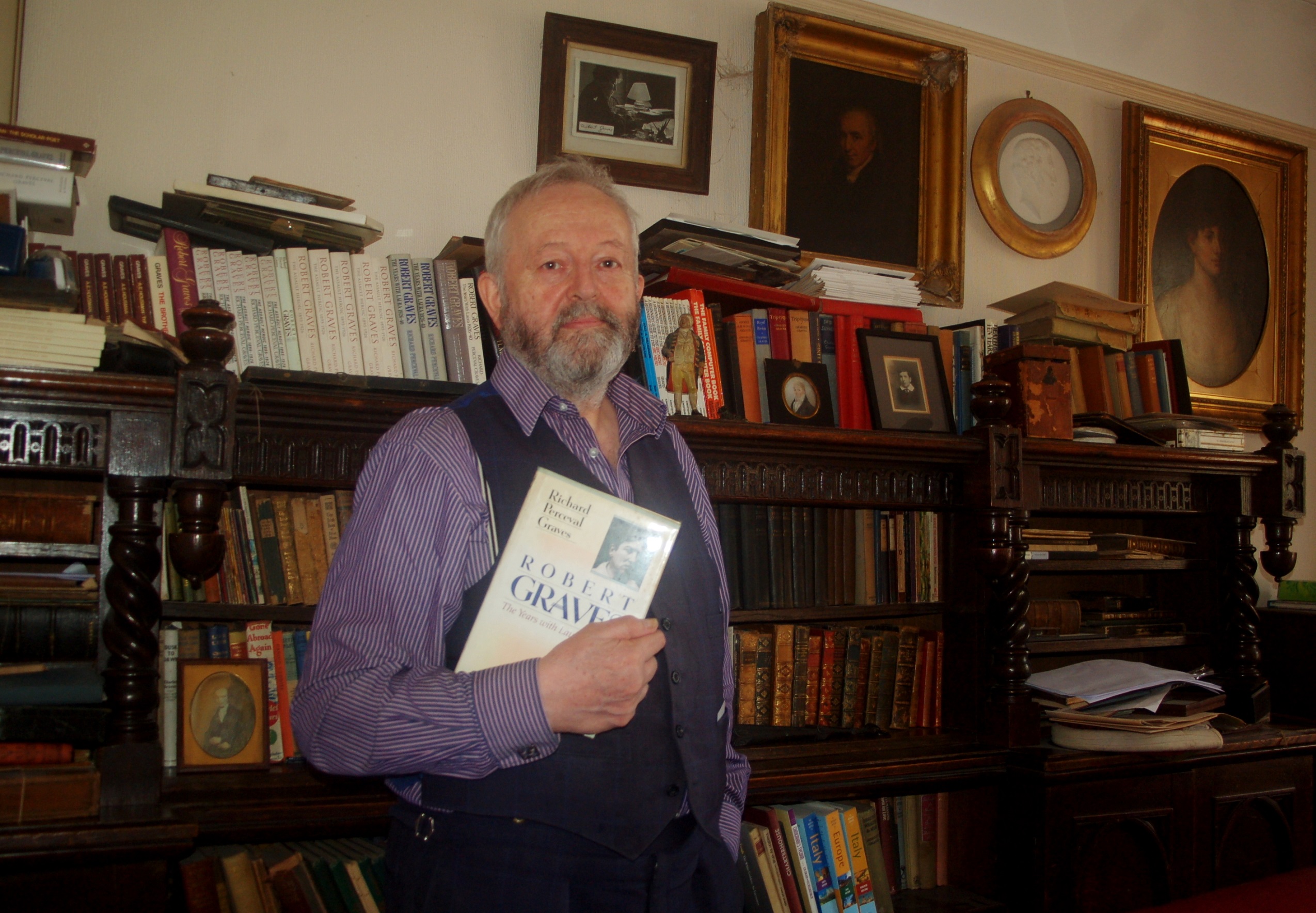

Richard Graves, of digital marketing agency GWS Media, has written a three-volume biography of his uncle Robert Graves – who served with the Royal Welch Fusiliers (RWF).

The RWF, the oldest military regiment in Wales, had the distinction of being the most literary regiment in the army.

Richard, who covers the period of The Great War in his book, The Assault Heroic, said: “I was privileged to know my uncle Robert for almost forty years.

“It is a great tribute to him that he succeeded in overcoming the shellshock that plagued him very severely for at least fifteen years of his adult life.

“He also succeeded, despite his intense suffering, in making such a remarkable contribution to English literature.”

The term ‘shell shock’ was coined by the soldiers but it was first used in medical literature, The Lancet, by Dr Charles Myers of the British Psychological Society in 1915.

Symptoms included fatigue, tremor, confusion and nightmares. Some soldiers received electric-shock treatment; some faced the firing squad for cowardice.

Graves, who had a holiday home in Harlech and whose poem Welsh Incident was inspired on a train trip in the area, began showing signs of shell-shock as early as September 1915. He drank ‘about a bottle of whisky a day’ to keep himself ‘awake and alive.’

After the war had ended, he described how there were times when ‘shells used to come bursting on my bed at midnight’ and ‘strangers in day-time would assume the faces of friends who had been killed’

Shell-shock affected Graves throughout his life. Symptoms subsided after he moved to Majorca, but returned when he began suffering from Alzheimer’s at the age of 81.

In Goodbye to All That, Graves wrote about the effect of shell shock and how an officer’s usefulness would decline. He said it had taken his ‘blood 10 years to recover’.

In his poems, Graves recounts waking visions of fellow soldiers who died on the Somme and survivor’s guilt.

Graves lived to the aged of 90, having written more than 130 volumes of poetry, fiction, essays, criticism and lectures.

His eldest son, David, would serve in the same regiment as his father, the Royal Welch Fusiliers (RWF), during World War II.

But sadly, David did not have the same lucky escape as his father and was shot in action in Burma in 1943. He was just 23 years old.

Richard, who named his eldest son David after the soldier, said: “It is one of the great sadness’s of my life that I never met my first cousin David Graves, who died heroically fighting against the Japanese in March 1943, not long after his 23rd birthday.

“He was not only the bravest of warriors, but he also wrote fine poems and painted exquisite water-colours. Had he lived, he might have achieved much both as a writer and as an artist.”

PTSD

The official view during World War I was that well-trained troops did not suffer from shell shock; only those who were unwilling or undisciplined.

The outbreak of World War II prompted Dr Myers to publish his findings of shell shock during the first war to create a better understanding of the condition.

Treatment evolved over the years and the documentary Let there be Light shows men undergoing hypnosis to treat ‘war neurosis’.

PTSD was first recognised as a mental health condition five years after the Vietnam War. A group of veterans, aided by psychoanalysts, lobbied the American Psychiatric Association to give a name to the suffering of people overwhelmed by the horrors of war.

PTSD appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980. It made way for greater research and attempts at finding effective treatments.

The condition, which is now understood to apply to civilians as well as those involved in combat, may include flashbacks, outbursts of anger and irrational fear.

PTSD in the 21st Century

Owen Morgan, 36, set up Man Cove Well-being to help inform and inspire men who have been affected by trauma or mental health issues.

Owen has personally experienced trauma – from physical abuse at the hands of a child-minder, to severe bullying and a life-threatening illness.

His site focuses on men, as it is believed they are less connected to their bodies and experiences, to help them to recognise trauma and ask for help where needed.

The massage therapist and personal trainer from St Mellons, Cardiff, said: “We share people’s experiences of trauma, as well as insights from specialists in the field, to help people recognise its affects and know that help is available.

“Trauma does necessarily have to be one major incident or be linked to fighting in a war. It can start in childhood or be a build-up of experiences over time, which affects mental, emotional and physical well-being.”

Owen’s trauma started when he was a young child, when his child-minder physically abused him and force-fed him.

It led him to have an unhealthy relationship with food later on and he was heavily overweight in his teens, then extremely thin and obsessed with fat percentage in his 20’s.

At the age of 32, he experienced stabbing pains in his stomach and lost two stone in weight in a week.

Doctors initially struggled to understand what was wrong with him as he was young, fit and healthy – regularly running marathons.

He was diagnosed Intussusception, which is a serious condition in which part of the intestine slides into an adjacent part of the intestine.

He had multiple organ failure and the dead intestine was removed – to save his life.The condition is very rare in adults and the doctors said stress and anxiety, which Owen had suffered badly with throughout his life, had affected his digestion and physical health.

Owen said: “It was a terrifying experience but I started to see how interlinked our physical and mental health is. From that moment I decided to take better care of myself, emotionally as well as physically.”

Owen started with mindfulness and finding ways to better connect with his body. He went on to set up Man Cove Well-being to help others.

He said: “We want to inform and inspire until the day comes when people are ready to ask for help.”